William Gay, Lines Better Not Crossed (Review)

William Gay heads the generous list of writers recommended to me by North Carolina folklorist Gary Carden. I read two of Gay’s novels in January. What little reading time I had over the next few months was dedicated to specific goals, but as the year warms toward summer, I anticipate the luxury of reading for pure pleasure again—and Gay’s oeuvre beckons.

A Tennessee Gothic writer, William Gay has been compared to Flannery O’Connor and Cormac McCarthy. I found an entry into O’Connor’s fiction through her correspondence, but I’ve been defeated twice by McCarthy’s bleak vision and austere prose.

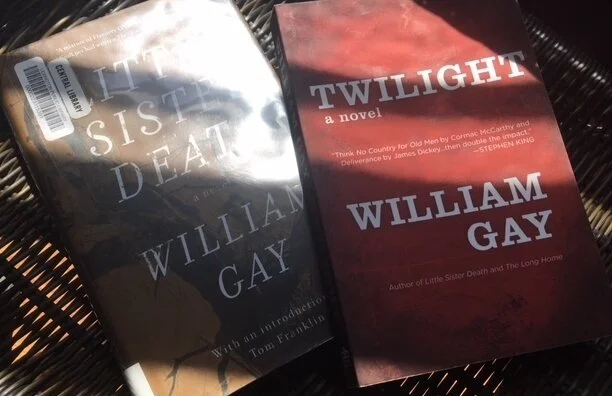

Gay’s work, on the other hand, grabbed me, and wouldn’t let go. A devotee of haunted house narratives, I started with Little Sister Death, Gay’s unfinished, and posthumously published, Bell Witch novel. Before I'd even finished it, I bought Twilight, his third novel, and the last to be published before he died. I carried the books around with me, reading any and everywhere: in waiting rooms and parking lots. Standing at the stove, stirring absently...

I flew through those stories, urged on by fantastic realms bordering the ordinary, recognizable world, Gay’s vivid imagery, and his often breathtaking prose. Like the domains of other Gothic writers, the forgotten corners of Gay’s Tennessee externalize and make visible the darker reaches of the human psyche, standing for one or more character(s) in some way. The language and legends of the hill country, the struggle between good and evil, and retribution—impending and inescapable—anchor his work in the American South.

Twilight pits Kenneth Tyler, an outraged innocent, against Granville Sutter, a brutal, middle-aged malefactor hired by the depraved undertaker whom Tyler has threatened to expose. Sutter’s attempt to intimidate the teenager meets with unexpected resistance, unleashing an inexorable sequence of tragedy, retaliation and escalating violence. Driven from his home and pursued by Sutter, Tyler escapes into the Harrikin, a semi-mythical forest exploited and abandoned by developers, and now grown wild. There, hunter and quarry leave behind “a world that still [adheres] to form and order…fleeing not only geographically but chronologically, for they [are] fleeing into the past.” Lyrical passages describe a perilous and haunted wilderness the boy must traverse to survive, and where he must finally confront the relentless killer. “There was more wickedness in the world than you thought,” pronounces a witchy old woman Tyler meets deep in the Harrikin, “and you’ve stirred it up and got it on you, ain’t ye?”

In Little Sister Death, David Binder, a writer struggling to recover his career, stirs up that wickedness by relocating his wife and young daughter to a haunted house and landscape. “Listen,” says the old man Binder asks about the property's nightmarish history, “somebody starts beatin on your door in the middle of the night you don’t have to get up and open the door, do ye?... What I am tellin you is you let stuff like that in.” And Binder does, literally, open the door to the house, and leave it standing open. He frequents sites that promise contact with the malevolent, and knowingly allows an unsuspecting family member to blunder into mortal danger. Seemingly powerless to resist the allure of the dark forces at work at the old homeplace, a farmhouse that still reverberates with echoes from the “Beale” witch haunting and the lurid murder/suicide of a farmer and his family who once lived there, Binder becomes an increasingly ambiguous character. By the tale’s end, he recognizes that he has changed since his arrival—the wickedness has found a home in him.

Gay’s universe is harsh, but it is just. The innocent are given preferential treatment, but bad choices, whether feckless or calculated, do not go unpunished. Oracles to those who have lost their way, Gay’s grotesques address prophetic utterances to his protagonists, but the characters face the consequences of their actions alone. “There’s things in this world better let alone,” as Tyler’s witch says. “Things sealed away and not meant to be looked upon. Lines better not crossed, and when you do cross em you got to take what comes.” Gay’s personal history is brought to bear in the conviction. He once visited the Bell lands with an uncle and aunt, whose disturbing experiences afterwards convinced them that the Bell witch had followed them home.

Twilight and Little Sister Death are both available from Dzanc Books.